The following was posted in advance of the launch of Toptal Scholarships for Female Developers. To support scholarship applicants, Toptal has also published a guide to making your first open source contribution.

Women are underrepresented in tech. This realization is nothing new. Just look at numbers released by Facebook, Google, Intel, Slack, and many, many more. But the numbers might be even worse than these reports imply.

At a recent tech event, I overheard a side conversation about the lack of gender diversity in tech. The small group was discussing the fact that even though women make up about 30% of the workforce in tech, higher level engineering teams rarely have more than a few women.

One of the participants in this conversation commented that this was because male developers are just generally more talented than female developers. No one in the group objected.

Hmm…

From personal experience at Toptal and my university experience in engineering at Princeton, which was nearly 50/50 male vs. female, I know this is false. I’ve worked with a number of incredible, profoundly smart female engineers in all kinds of roles. Yet the numbers don’t seem to match my own experience, especially when you start looking at more senior engineering roles.

And addressing this disparity is important. It’s not just diversity for the sake of diversity. If men and women are equally intelligent, statistically speaking, then out of the smartest ten people in the world, five should be male and five should be female. Thus, if your team is anything less than an equal balance of men and women, then your team is probably not the best it can be.

If your team is anything less than an equal balance of men and women, then your team is probably not the best it can be.

In a perfect system, diversity is a probabilistic result. But these aren’t the results we’re seeing.

After overhearing this conversation, I wanted to take a look at numbers to better understand if/where software team building tendencies were going wrong. I searched Google for trends in the gender breakdown across skill levels in software engineering, but I wasn’t able to find much, so I decided to look at the publicly available data on GitHub. I scraped 5,000 profiles to get names, number of followers, number of contributions, and number of repositories. I then used the open source package genderize.io to figure out the gender of each profile.

There were so few women in this first batch that I had to add more data to make even simple graphs significant, so I scraped 15,000 more.

Here’s what I found:

Is Open Source Open to Women?

Open Source Is Dominated by Men

Even before getting into any further analysis, it was obvious that the percentage of women was extremely low. Of the 20,000 profiles, genderize.io was able to confidently determine the gender of 15,374. Of those, just 6.0% (926) were women. The disparity gets more severe once you start taking a look at user activity.

Let’s take 10 contributions as the cutoff for the difference between a user who has just created a profile and maybe experimented a bit and one who has at least delved into an open source project or started their own. The result: 5.4% women.

Just 5.4% of GitHub users with over 10 contributions from our random sample are female.

In fact, if we divide users into buckets according to their number of contributions (with a minimum of 1,000 users in each bucket), the percentage of female users tends to decrease as contributions go up.

Not only are there far fewer females on GitHub than tech industry gender diversity numbers might suggest, but it looks like the percentage of females decreases as user activity increases.

I kept digging, looking at gender across number of followers and number of repositories, and observed the same trend. This was especially clear when looking at the number of repositories:

Again, we see that the percentage of females decreases as we move to buckets with more repositories.

So what’s going on here? Is GitHub activity a reasonable indicator of programming expertise in the first place? (I think it is.) Are talented female engineers less likely to actively contribute to open source than their male counterparts? Are these results another indicator of the tech industry’s entry/retention problems when it comes to female engineers?

Why Are the Numbers in the Open Source Community So Low?

Numbers for women in the tech industry are already pretty bleak, but they’re even worse in open source projects.

A lot of previous research has focused on the reasons why women are not willing to embark in STEM-related subjects and careers. Some conclude a general lack of interest in STEM subjects. Others believe women decide against pursuing STEM careers after being stereotyped by family and teachers. Still others cite a lack of role models or a combination of multiple causes.

According to a study on gender in StackOverflow, “The issue of gender and STEM-related subjects has been studied for several years, and mostly from the point of view of ‘why’ women do not engage with scientific studies or careers. Lesser attention has so far been given to quantify the phenomenon and representation of women in online communities (as technology-‘users’), what are their levels of participation, and whether differences can be detected at the gender level. Only anecdotal evidence has been gathered on how specific communities actively discourage women from participating.”

But when we spend so much time focusing on why there are fewer women pursuing STEM-related subjects, we lose focus on another important disparity: if 28% of CS masters degrees go to women, why are the numbers in the open source community so much lower?

There are a few possibilities to consider when thinking about an answer to this question:

1. Maybe there isn’t a strong correlation between programming talent and GitHub activity.

In the tech industry, many developers go to GitHub early in their careers as it’s a prerequisite to be taken seriously. However, it seems that fewer aspiring female developers view open source this way. Is it possible that this data is all coincidental and does not mean much in relation to the number of talented female software engineers in the tech industry?

I discussed the question with two engineers at Toptal, Anna-Chiara Bellini and Bozhidar Batsov. Anna-Chiara has over 20 years of software engineering experience across a variety of academic and business settings, and Bozhidar is number 98 on the list of most active GitHub contributors in the world.

Both agreed that while being active on GitHub is typically a good indicator of engineering expertise, the reverse isn’t true, mentioning that they know plenty of great engineers who aren’t involved in open source at all. The tech industry agrees too, with many companies assessing GitHub profiles during hiring processes (although this practice seems to be quite biased, which isn’t really a surprise given the results of my study).

GitHub activity is generally a good indicator of engineering expertise, but the reverse isn’t true… Plenty of great engineers aren’t on GitHub.

Bozhidar suggested that open source contributors are often more likely to be the type of people who push for big internal changes in a company setting. Anna-Chiara commented that it takes a great deal of confidence to contribute to open source, something that she thought may be more difficult for female developers to overcome, given the tech industry’s poor history with welcoming women.

There are certainly several biases that could potentially be at play with this GitHub data (including the fact that almost 25% of the names couldn’t be classified as male/female with confidence).

However, Bozhidar, Anna-Chiara, and I agreed that GitHub activity level is generally a good indicator of programming expertise. Yet this data suggests a trend of talented female programmers choosing to discontinue (or never start) their open source pursuits in favor of other options.

2. Numbers cited in tech company reports include non-tech roles.

Many companies in the tech industry cite that they employ between 25 and 30 percent women. This number, however, can be misleading. Most of these larger numbers – yes, they are the larger ones – include both technical and non-technical roles.

As you begin to examine the percentage of female employees in technical roles, the numbers drop even lower.

At Facebook, 32 percent of employees are female, but only 16 percent of technical roles belong to women. At Google, there’s a similar drop of 30 percent female employees in the company as a whole to 18 percent in technical roles. Slack drops from 39 percent female overall to 18 percent in engineering roles. Of the companies I’ve examined, Intel has the smallest jump, going from 24.1 percent female overall to 19.4 percent in technical roles.

So even though many companies boast a percentage of female employees that is about a quarter or even a third of the company, the number of women in technical roles is actually much lower. It seems that claims of 15 to 20 percent would be more accurate.

But that still leaves a huge disparity between the percentage of women involved in technical or engineering roles at tech companies and the percentage of women who contribute to open source projects on GitHub.

3. Female programmers are leaving the tech industry.

If activity on GitHub correlates with seniority and expertise, then the extremely low number of active female contributors (low even compared to female contributors overall) could be explained by the alarmingly high departure rate of female engineers from the tech industry.

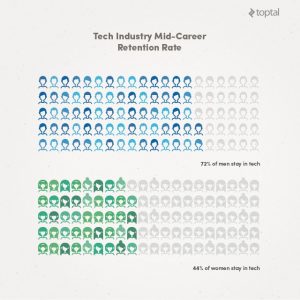

Among women who join the tech industry, 56 percent leave by mid-career, which is double the attrition rate for men.

If the tech industry can’t retain as many women past their mid-career mark, then it’s likely that they won’t be contributing to many open source projects either.

But this line of reasoning also begs the question: Is the correlation between seniority and contribution actually true? Many frequent OSS contributors are relatively new programmers who are trying to establish a name for themselves – so where are the women from that group?

4. GitHub can be an unwelcoming community for female programmers.

Commenting on an article about women in tech, one female developer says, “In regards to the open source projects – I’ve been thinking about this recently. I actually haven’t committed to any and it definitely puts a kink in my career… I feel like it’s a circle I can’t get into. But mostly I fear the excessive spotlight of being a sole female programmer on a publicly available project. In light of how women are treated on the internet, this fear does not seem unreasonable.”

Anna-Chiara believes this kind of apprehension is a common theme amongst female engineers, especially when it comes to OSS. When I asked her if she thought women were less likely to contribute to open source projects, she responded, without hesitation, yes.

Anna-Chiara also brought up the possibility that female GitHub users might try to adopt a gender-neutral or male name to ensure they would be taken seriously (remember that genderize.io was not able to confidently determine the gender of about a quarter of the profiles scraped).

That does not mean, however, that female contributors are not out there. Bozidhar brings up Exercism.io, a popular project started by Katrina Owen that has several female contributors. He also mentions Bodil Stokke, a female developer from Norway with an extremely extensive history of popular open source contributions.

Anna-Chiara also suggests that if a project had women among the top contributors or leaders, female developers might be more likely to contribute to it. Unfortunately, compared to the number of male-dominated projects out there, female-led OSS projects are hard to find.

But the issue is larger than just OSS. “If I think of the women I know in development, it’s nowhere close to the 20% that you hear about at these big companies. I don’t think it’s even anywhere close to 10%,” Anna-Chiara tells me. “The result of this analysis of GitHub doesn’t surprise me.”

5. Implicit biases that shape the tech industry might be trickling into GitHub.

Eric Ries points out problems of implicit biases in the tech industry. Even if individual people within systems are not biased, it is still extremely easy for those systems to become biased. People also have unconscious biases, which complicates the issue even further.

In his article, Eric uses the example of orchestras, which were primarily all-male until the 1970s. People believed that male performers had a superior aptitude for music than female performers. However, once orchestras started separating musicians from judges with a physical screen during auditions, the numbers shifted significantly, and people began to accept that men and women played equally well on average.

If similar biases come into play with hiring systems in the tech industry, it could help explain the smaller percentage of female software engineers that I discussed earlier. And if fewer female software engineers are being hired, those effects could trickle into open source communities like GitHub. If someone is rejected for full-time programming roles, they might come to believe that they are not as talented, and would therefore be less likely to have the confidence to contribute to open source projects.

Where does this leave us?

Here are some follow-up questions that come to mind for me (and there are plenty more):

1. How are these numbers changing over time?

Getting more women involved in the tech industry is a highly-discussed topic right now, and the rise of coding bootcamps that require contributions should have a positive impact, including when it comes to open source. How effective are those discussions and the various new initiatives? What would these numbers look like 3 years ago? 5 years ago? What about in a year?

2. How else can we analyze GitHub data?

Anna-Chiara suggested examining the gender breakdown of users based on the number of forks they have to get an idea of how frequently female GitHub users are experimenting with a project in some way. Additionally, there are other factors at play, such as age group, that might affect our findings. Open source has been a staple of the tech industry for a long time, but GitHub was only founded in 2008.

3. Is there a good way to look at which GitHub users are employing a fake name?

If the percentage of women that use a fake name is much higher than the percentage of women on GitHub overall, that would make a very strong statement about how welcoming GitHub (and tech in general, to a certain extent) is as a community.

4. How do these numbers change when you start looking at location?

This is imperfect, as interaction on GitHub is theoretically location-agnostic. But can we learn anything from the tech communities in countries that have a proportion of female GitHub users that is higher than average.

And here are some ideas for improving these numbers (again, there are of course plenty more):

1. Can the pages of popular GitHub repositories be improved?

When I discussed this topic with Bozhidar, he mentioned that most projects/communities on GitHub have leaders who are extremely patient, welcoming, and happy to guide new open source contributors through the early stages of the project. This does not seem to be common knowledge at all (remember the aforementioned comment from a female developer who felt that open source communities were “a circle [she couldn’t] get into”).

Are new GitHub users aware that this type of mentorship and support exists (assuming that it’s as prevalent as he says), and would a new user know how to easily find such guidance? Could improvements be made to the interfaces of popular GitHub repositories to make this more obvious and make them more welcoming? For example, if popular repository pages included something like an official “Repository Mentor” role, maybe it would be much clearer that a welcoming, experienced user was available to answer any questions.

2. Publish better (and more prevalent) “Getting Started with GitHub” guides.

There are plenty of posts out there that teach you how to use GitHub by walking you through pulls/pushes, commits, branching, and more, but I find next to nothing in terms of guidelines for interacting within the GitHub community (if you know of any, please post relevant links in the comments).

A how-to guide for navigating GitHub community etiquette and best practices according to your skill level might help to break down the intimidation and spotlight elements of contributing to open source. This is definitely something that could encourage more aspiring new developers to get involved. Stay tuned for a guide like this from Toptal.

3. More mentorship could make an enormous difference.

Bozhidar commented on the importance of developers involved in the project who were willing to help newcomers get started with basic tasks, while Anna-Chiara discussed how it could be quite intimidating to jump into a project and open your work up to criticism. It seems that there is a great deal that could be done to make open source communities more welcoming for everyone, including women. Stay tuned for an initiative from Toptal here as well!

Are you surprised by the results from GitHub? What do you think they mean?

San Francisco Employment Law Firm Blog

San Francisco Employment Law Firm Blog